“Gardening, not architecture,” reads one of the phrases from Oblique Strategies, a deck of cards created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt to assist with creativity. Jeanne Gang, founding partner of Studio Gang, attempts both in her book, The Art of Architectural Grafting, which offers “rules for extending museums and anonymous buildings to increase their usefulness and delightfulness and reduce their carbon pollution.” Published by Park Books, her volume digs into popular ideas about the urgency of adaptive reuse, arguing that the work of architects should be less about razzle-dazzle and more about sharing and caring.

The Art of Architectural Grafting could be described as a gentle manifesto: It contains theory, history, work by Gang’s students, built projects, unrealized case studies, and personal reflections. Beginning from the horticultural practice of grafting, which involves taking a scion cut from one plant and growing it atop a rootstock from a separate plant, Gang goes on to deliver the ten points of the architect-grafter’s credo and share how the idea is put to work throughout Studio Gang’s portfolio. The publication also shines a light on what we could do with the background buildings that largely comprise American cities.

AN’s executive editor, Jack Murphy, spoke with Gang about her new book.

AN: Your thesis about grafting is powerful because it is both something that architects have done for a long time, and it is also part of a new wave of thinking about how to design buildings. How do you connect those trends?

Jeanne Gang (JG): Grafting is absolutely something that architects have done in the past. When I first started preparing courses on reuse, I was at the American Academy in Rome. It was perfect to be in Rome during this time because there are examples of reuse everywhere—not just in buildings, but also with their components.

While the idea of reuse has always been around, the book reframes and broadens it. In the U.S., we see lots of relatively young buildings demolished and replaced entirely. At a time when we’re facing a climate crisis, we need to urgently think about how to regenerate our existing building stock. It shouldn’t only apply to iconic buildings, but also anonymous buildings, because they are valuable if you put a cost on their embodied carbon.

Grafting also makes for more interesting architecture because it produces a form of asynchronous collaboration between the original architects and those who come after them. This is a form of continuity that’s lost if you just replace the building completely, which is typically perceived as the easier option in the U.S. In Europe, where there’s much less of an appetite for change and a stricter approach to preservation, we see the opposite problem: There is a resistance to adding onto existing buildings with new architecture. The two cultural contexts have different constraints.

AN: Can you tell me a bit about the graphic design of the book? I like how it looks like an atlas.

JG: We worked with Elektrosmog on the book’s design, which was inspired by the many historic guidebooks and gardening guides I came across while researching at different libraries. The long title and the shape of the smaller essays interspersed throughout the book are some of the ways we paid homage to these archival inspirations in the design.

AN: The book is personal at times: You write about your own memories and experiences. It also seemed like your time and work in France impacted your thinking. Can you share about that influence?

JG: It’s all a bit organic. I was in France as an exchange student and then worked on the Maison à Bordeaux while I was at OMA. What really brought me back there was the international competition for the Tour Montparnasse, which focused on redesigning this monolithic tower from the 1970s. I spent a lot of time in Paris while we were working on our submission, which sadly came in second. However, I enjoyed working in this different context, and, in 2017, we expanded the practice with our first international office in Paris. In November, we’ll complete our first project in France: the University of Chicago John W. Boyer Center in Paris.

AN: Another aspect might be the influence of Bruno Latour. How was his writing useful to you?

JG: His writings have been influential for me. He beautifully combines science and the humanities to articulate social and political issues that help us to address climate change. I discovered his writing back in the early 2000s, and it was like discovering a special map that helps you navigate your way through a situation but also allows you to chart new pathways relevant for design.

AN: One thing I liked about the book is that you introduced the work of other architects as precedents. There are lessons from offices about how reuse can be done artfully. What did you learn from practices like Lacaton & Vassal?

JG: I found lots of practices who think this way—as grafters. Frankly, many more people could have been included. One of the many things I appreciate the work of Lacaton & Vassal is that even when forces work against them, they find ways to creatively reuse buildings. Carlo Scarpa is another one of my personal favorites.

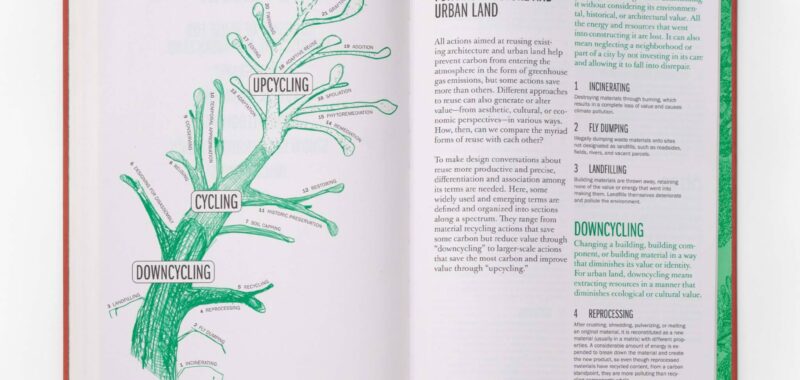

Even though the work of reuse exists, I was concerned about the lack of precision and nuance in the way we talk about it. So I wanted to help change that by adding new language around it, which the book does, especially in the chapter about techniques for joining. Designers need to be more precise about what exactly a project does when it reuses something. If we can better articulate these ideas, then we can explain and clarify how grafting can be deployed.

AN: The diagrams were helpful, because part of being a grafter seems to be looking closely at what already exists and taking an inventory. Designers ought to stay close to the material conditions in which they’re working.

JG: In teaching and practice, when we start a project, I tell students or team members, “You have to find something you love about the building you’re working on.” That appreciation for what’s already there must come out in the drawings. If you keep the existing structure at arm’s length, then you won’t find the best solution; you have to find the connection point.

AN: The book includes case studies from Studio Gang. How are these ideas implemented in the office’s design processes?

JG: Not all our projects begin with what’s already there. But for the ones that do, we now have this book. Having a shared language about grafting is helping us be clear about our approach during the design process, particularly for projects where there have been multiple previous additions by different architects. Teams can refer to examples in the book to better communicate with each other in a more precise manner. We also try to stretch the concept to different scales of projects, including urban design.

AN: Can you say more about the Bark Belt project at the end of the book? It reads like a provocation for architects to move beyond working on buildings to designing systems.

JG: When grafting to add capacity onto existing buildings, using timber is a good choice because it’s lighter and lessens the load on the existing structure. But the issue we’ve run into with timber is that there often isn’t a lot of timber near the cities where we build, so the material travels from far away. The Bark Belt project studies how to remediate the postindustrial landscape of the Midwest and create new local forests that could supply timber for nearby buildings. At Studio Gang, we are exploring how to create a pilot forest project. Perhaps later it could be a useful model for other biomaterial systems—not just trees, but maybe other plants that also remediate soils while providing new building materials. And, yes to designing systems: To effectively respond to the climate crisis, architects will need to increasingly think beyond the building.

AN: What are your thoughts about the rise of mass timber in the U.S.?

JG: We must work on every single possibility to reduce carbon emissions, whether it’s bio-based materials or low-carbon concrete. For the David Rubenstein Treehouse on Harvard’s Enterprise Research Campus, which is under construction, we’re using mass timber for the structure and a low-carbon concrete for the foundation. It’s hard to get over the hump because nobody wants to be first in taking a risk on new construction techniques.

Some people are solely interested in mass timber, but I think we must work on all fronts, including solutions to replace cement in concrete. For timber, though, we need to become more sophisticated about the supply chain, how trees are grown and harvested, and how forests can be designed to bring multiple ecosystem benefits. Forests shouldn’t just be a monocultural farm.

AN: What do you hope the impact of this book will be?

JG: In the U.S., I hope it will be useful for architects who want to make the case for reuse and prove its value against building from scratch. In Europe, I hope it will foster more acceptance of additions that are more than just replicas of what is already there. Buildings should have a chance to live as long as they can, and people need to have new spaces for new ways of living.

AN: What are you optimistic about?

JG: Everything we have is material that can inspire the next generation. Now, when we’re designing something new, we try to imagine how someone could add onto it in the future. For me, this moves architecture away from being a work of art frozen in time and liberates it as an unfolding, ongoing process that will have multiple authors and many identities over its lifetime.