Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana by Virginia Hanusik | Columbia Books on Architecture and the City | $28

I had lived in New Orleans for five weeks when Hurricane Ida hit. I was lucky enough to evacuate to a friend’s house in Houston, where my wife and I stayed until the power in our neighborhood came back on. At that time, much of south Louisiana was still without electricity. Traffic was heavy on the drive back from Houston, and by the time we approached New Orleans on I-10, it was pitch black, the darkness unbroken by house or street lights. Until, that is, the sky was lit bright orange by flares from the refineries that line the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. We now know that the electrical outage meant that the refineries were flaring improperly, spewing even more toxins than they are legally allowed to into the night sky. The apocalyptic light of those post-Ida refineries made for a spectacular image of environmental injustice.

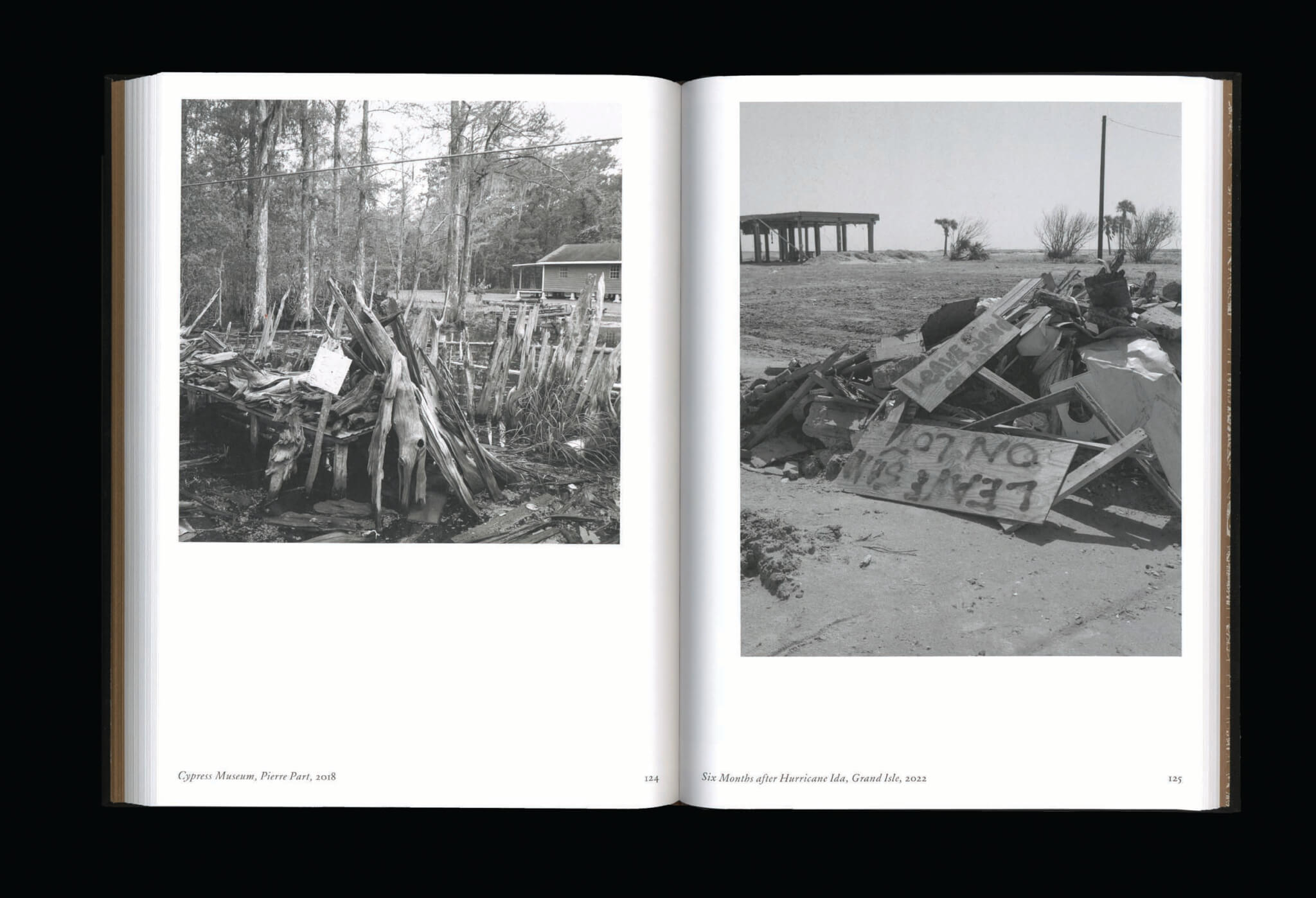

Virginia Hanusik’s new photo book, Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana, aims to divert our attention from such spectacle to the everyday impacts of climate crisis. Over the last decade, Hanusik’s photographs of South Louisiana have been featured in magazines like The New Yorker, exhibited across the country, and gained her a following on X. In her book, signs crop up over and over. They read, “Warning/Do Not Anchor or Dredge/Crude Oil Pipeline”; “Welcome/You Have Reached the Southernmost Point in Louisiana/Gateway to the Gulf”; “Century 21/Action Realty, Inc.”; “Leave Sand on Lot”; and “Growing Louisiana Together/#MakeTheFuture,” with a Shell Oil logo. These everyday signs mark places, boundaries, and transactions, but they also tell stories of persistence, evacuation, destruction, exploration, extraction, and exploitation.

Hanusik’s book aims to show what literary scholar Rob Nixon calls the “slow violence” of climate change, the “chasm that divides those who can act with impunity and those who have no choice but to inhabit intimately, over the long term, the physical and environmental fallout.” Unlike interpersonal or military violence, slow violence is often invisible, and Nixon poses how depicting it can save the world. No pressure. In the introductory essay to Into the Quiet and the Light, Hanusik positions her own work similarly: “advocating for the value of a place that is often seen by the rest of the country as a sacrificial climate buffer zone.” Making South Louisiana visible, she posits, will push us to take this place, and the havoc climate change is wreaking on it, seriously.

Much of Hanusik’s oeuvre is spectacular. There are pink and orange sunsets over Lake Pontchartrain, palmetto palms in early-morning fog, narrow strips of swamp against the silvery blue vastness of the Gulf. But the photographs chosen for Into the Quiet and the Light admirably support her foregrounding of the everyday. They show landscapes that interweave the human and the nonhuman: Lake Maurepas with a crumbling pier; a tarp-covered A-frame roof; the moon rising over the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier. Most notably, they are printed in black and white. This desaturation stops viewers from either basking in the glow of expected beauty or crying out in horror at the sublime destruction of, say, Edward Burtynsky’s immense oil fields and Blade Runner—orange mine tailings. Instead, it invites us to look more closely and ask ourselves what stories these places tell, whose lives are intertwined with them, and what their future will be.

Hanusik’s essay directly addresses one of my discomforts with her photographs: If she aims to refocus from grand images to everyday life, why are there no people in her photographs? She argues that “the built form holds collective memory, that it often has more power to describe how we view the land and each other than portraiture can.” In support of this argument, a footnote cites Colorado photographer Robert Adams to the effect that, while he was photographing, his questions about landscape survival often “fell away into the quiet and the light.” The quote gives Hanusik’s book its title. I’m not convinced, though. What Adams describes is a flow state of artistic work, and he implies that his immediate experience supersedes his intellectual questioning. But this immediacy is precisely what Hanusik aims to avoid or, at least, move beyond. Built form can hold collective memory, yes, but it is always at one remove from individuals. Hanusik’s elegant portrait photographs from other publications clearly show that she can avoid her subjects becoming mere extras in a disaster story, and I think such photographs would have fit this book well. That said, her wonderful photography of South Louisiana’s architecture, much of it raised high above ground (and hopefully water) level, deserves a book of its own.

Into the Quiet and the Light deviates from the standard monograph that presents one artist, with at most a few laudatory essays from critics. Instead, it is like an episode of Greek tragedy, one in which the character (Hanusik) interacts with a chorus of other voices. Photographs alternate with brief essays by activists Imani Jacqueline Brown, Jessica Dandridge, and Michael Esealuka; writers and educators Billy Fleming and Andy Horowitz; and designers such as Kate Orff and Jonathan Tate. This move is central to the book’s success. Only a few essays engage with Hanusik’s photographs, and each of them could stand alone with its discussion of South Louisiana, climate change, and/or landscape representation. Word and image complement each other, and the book’s small format makes it easy to hold and read. Although it is beautifully made—don’t miss the endpapers, which are based on Louis Fink’s famous meander map of the Mississippi—this is as far as a photo book can get from belonging on the coffee table. Into the Quiet and the Light argues that art can only depict slow violence and serve political change if it can be in dialogue with other fields. It makes two valuable contributions: first, giving us Hanusik’s photographs at their least spectacular and most laconic and, second, modeling a collaborative and place-specific approach to depicting climate change.

Alexander Luckmann is a PhD student in architectural history at UC Santa Barbara. He writes about the built environment and lives in Santa Barbara and New Orleans.